Introduction

Although we know of wars and the mess of human devastation it leaves in its wake— often times the most terrifying inflictions are those actions which leave nothing but silence—- no evidence or closure. Nothing but questions and a hope for a sort of resolution. According to Held Hostage: Analyses of Kidnapping Across Time by Seth Loertscher and Daniel Milton from The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point,

» There has been a worldwide spike in kidnapping events since 2003. The trend is global and not confined to one specific region.

» The overwhelming majority of kidnappings are domestic (intra-state)

These findings are also echoed by the U.S State Departments OSAC Global Kidnapping Assessment. A report released in 2013 explains,

“The threat of kidnapping occurs throughout the world. In many cases, political instability, weak institutions, and inadequate or insufficient law enforcement capacity are common factors that create a security environment conducive to kidnapping. Within any one country, the danger is seldom uniform, and certain sub-national regions appear more prone to kidnapping than others.”

In addition to these factors is the unreliability of reported data attributed to precarious factors like civil opinion of law, fear of reprisal, and human error. The OSAC assessment details:

“Estimates on the number of kidnappings worldwide range drastically. A significant percentage of kidnappings go unreported due to the reluctance of victims and their families to seek intervention by authorities; this may be due to the threats made regarding such intervention, the perception that law enforcement would be ineffective at resolving the situation (and could

possibly make it worse), or the belief that police are actually complicit in the kidnappings. It is also difficult to put a precise number on kidnappings, because they are often classified as related crimes.”

Focus and Data Used

Although data on kidnappings is clearly far from perfect—- there are sources that exist that try their best to report as much as they can find with reliable checks and safeguards in place by way of researcher reviews, realtime editors, and curators who monitor reported events daily.

The source of choice for this study is the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project which receives financial support from the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations at the United States Department of State, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the German Federal Foreign Office, the Tableau Foundation, the International Organization for Migration, and the University of Texas at Austin.

ACLED data is derived from a wide range of local, regional and national sources and the information is collected by trained data experts worldwide. For more information on the terms in this report please consult their codebook found here. Per their terms they define abductions as:

An actor engaging in the abduction or forced disappearance of civilians, without reports of further violence. If fatalities or serious injuries are reported as a consequence of the forced disappearance, the event is coded as ‘Attack’ instead. Note that this sub-event type does not cover state-sanctioned arrests, unless they are reported to have been conducted extra-judicially. By contrast, non-state groups can never engage in arrests, and their activity engaging in “arresting” is typically coded as such.

Main Questions

Using Libya, Yemen, and Iraq as a case study— how do abductions relate to other events in these regions?

What is the proximity of abductions to these events, and on an aggregated level—– how are they correlated?

Methodology

The data being explored is from a time beginning January 2016 to April 30th 2020. Although ACLED has over 25 different classifications of event types—- I chose 11 that I thought would be interesting to explore.

Event Types

- Peaceful Protests

- Abduction and Forced Disappearances

- Air Drone Strike

- Armed Clash

- Excessive Force Against Protesters

- Violent Demonstrations

- Arrests

- Remote Explosions/Landmine/IED

- Agreements

- Change to Group Activity

- Government Regains Territory

Four Phases of Investigation

The study is broken into four main facets.

- A spatial study of proximity between events, including a mean minimum distance analysis— and a comparison of directionality.

- A correlation study of the 11 variables and how they are related to one another

- A spatial regression model

- A normal regression model without spatial consideration

1. Distance and Directional Analysis of Other Event Types to Abductions

Usually interest in spatial point data revolves around two

main questions:

1) Is there a pattern to the data?

2) If I have a bunch of classified spatial points—- How can I tell if they are related to one another is some way?

This portion of the study uses three statistical methods to help us answer the questions in a visual way.

Shape and Density

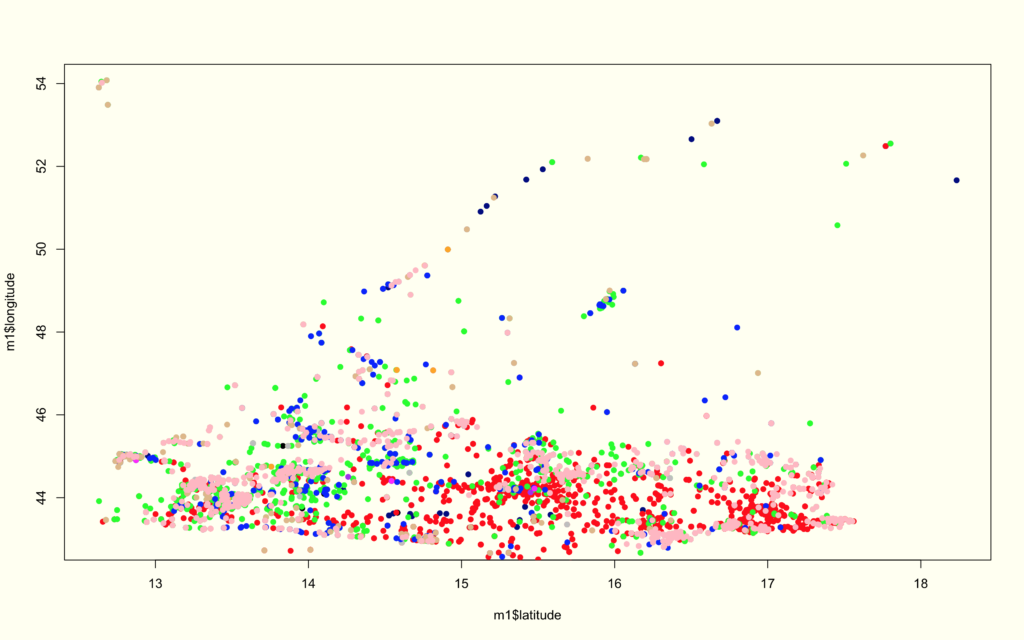

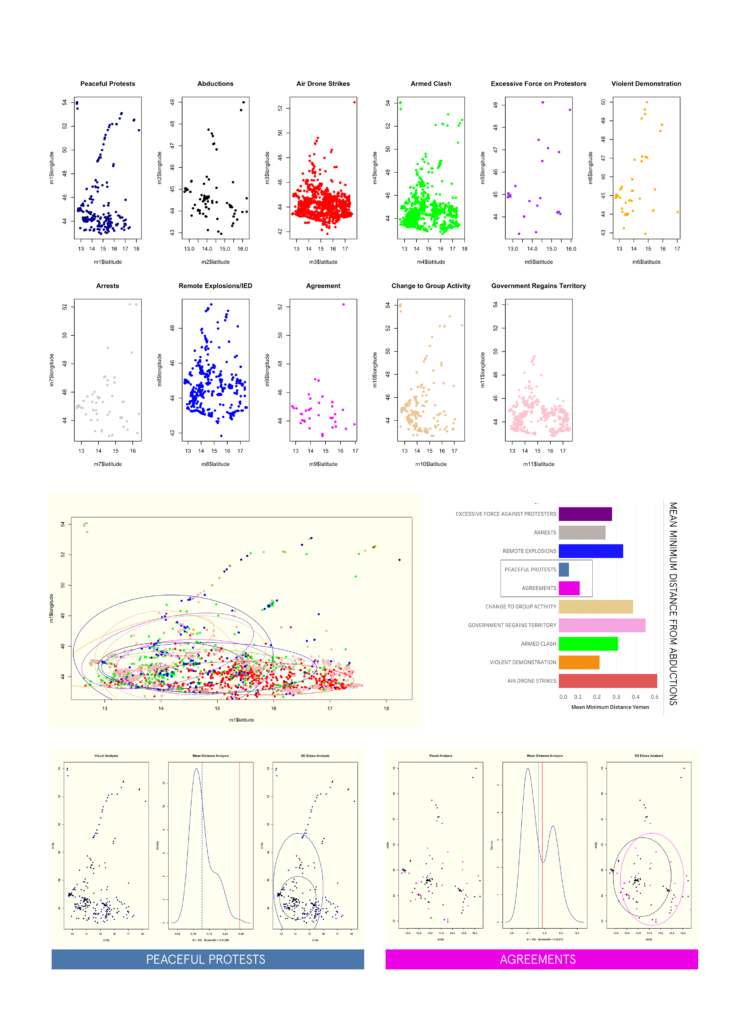

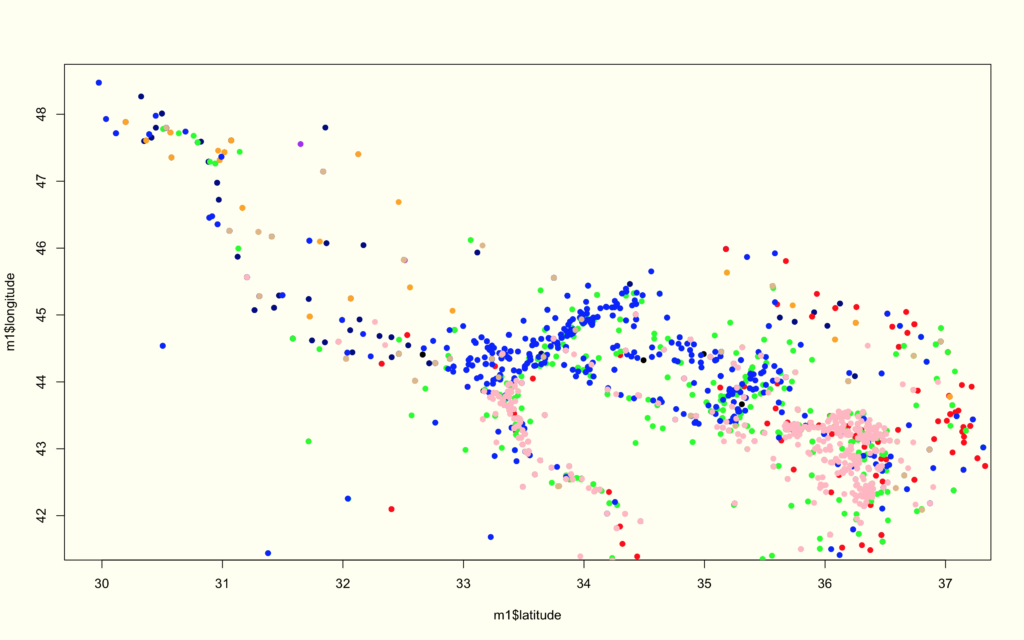

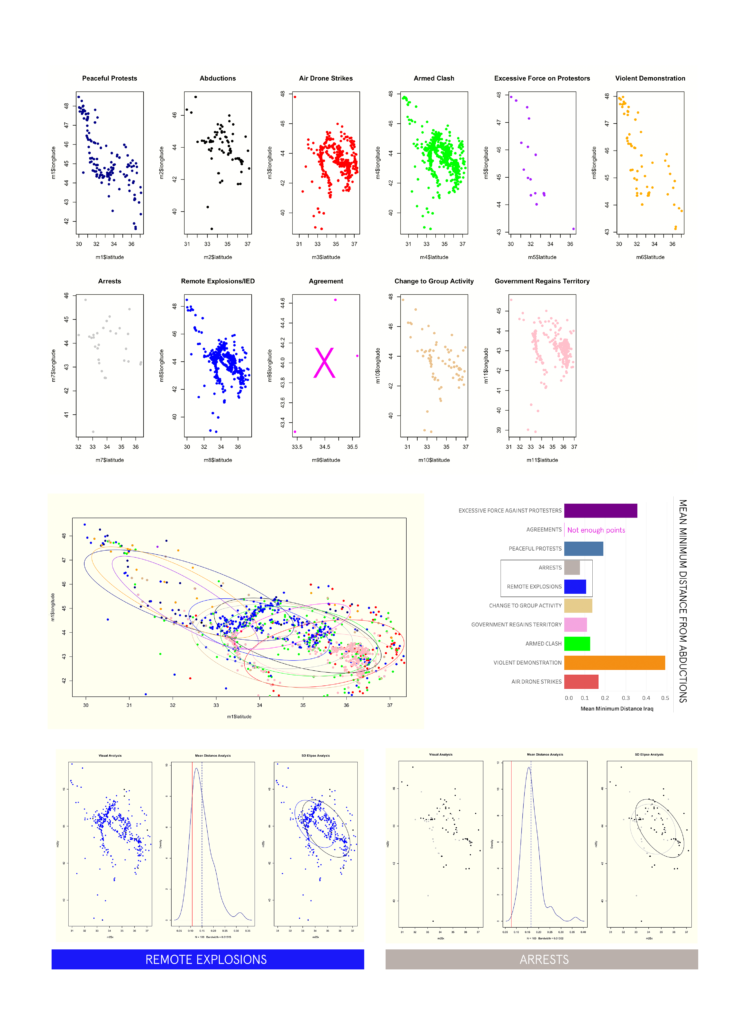

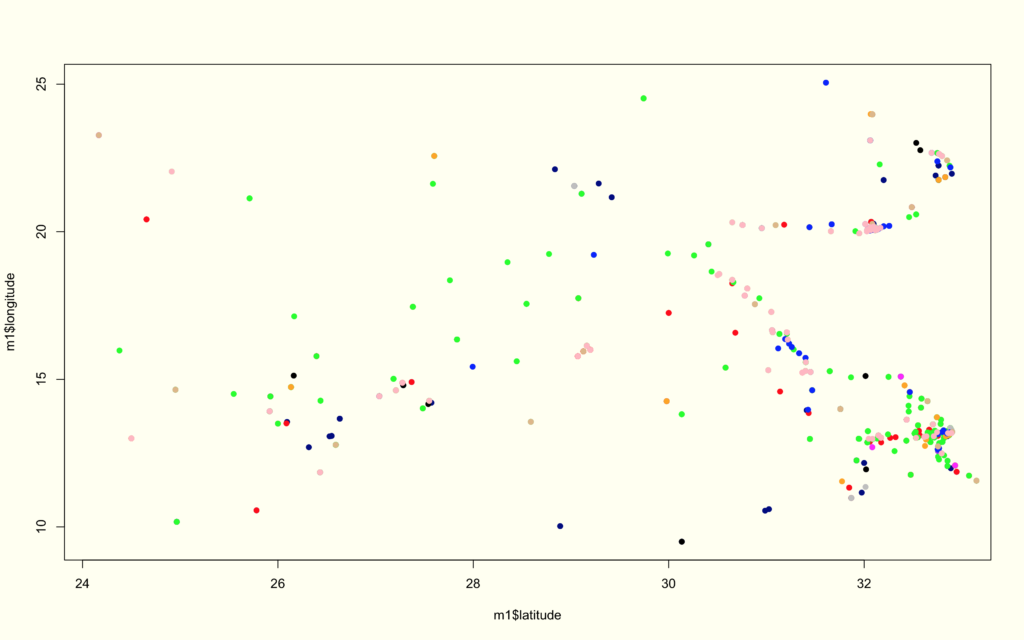

The first part of this analysis is purely about the shape and frequency of our event types, as well as, the directionality. The first graph plots all the event types for the region over the 4 year period. Below this graph is essentially the same information broken into subplots and color classified by the event type—- this is great way of discerning how certain events cluster when compared to others, as well as, the differences in density/sparsity.

Directionality and Distance

The second part creates what is called the standard deviation ellipse. This is in effect a directional 2 dimensional version of standard deviation. A

very helpful tool for identifying directional information about spatial point data in an easy way that can aid in assessing if groups of spatial points are related. In this case an ellipse is created for each event type.

Also included— is the calculation of mean minimum distance for each event group related to abductions. The lowest mean minimum distance is a type of indicator for event types which may be happening in closest proximity to kidnapping and abductions.

Simulation of Mean Minimum Distance

This study goes one step farther by choosing two events with the lowest mean minimum distance to abductions and runs a randomized simulation on those points.

Why do we do this?

It gives a better indicator of how closely related event point clusters are to abductions in a way that is more holistic. The graph titled “mean distance analysis” represents the results of this simulation. The red line is our actual mean minimum distance of the two point groups— and the dotted line is the re-calculated distance after artificially assigning points over many iterations. The closer they are would indicate how spatially, and statistically related they are. A wider gap would mean there is a significant difference in shape and distribution of the two point groups in spite of low mean distances.

RESULTS

YEMEN

IRAQ

LIBYA

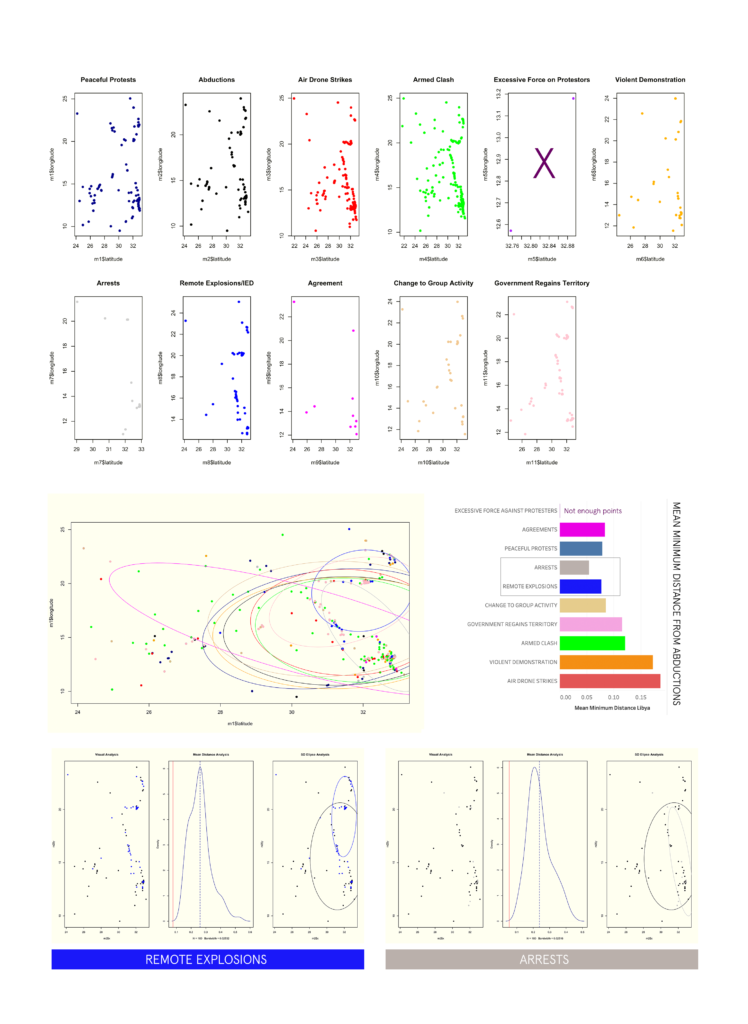

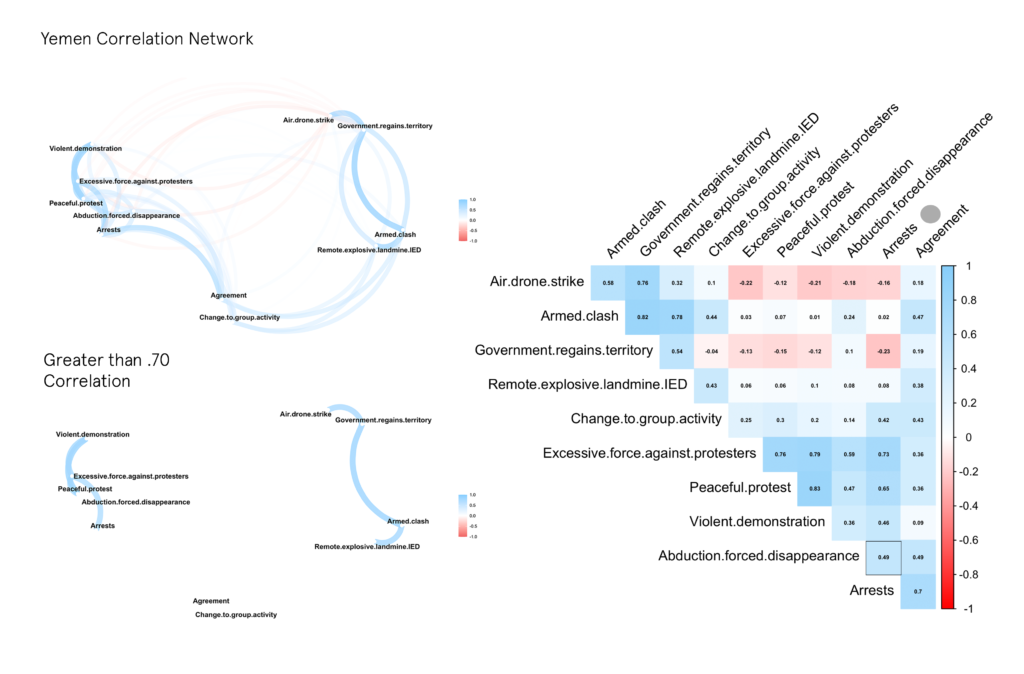

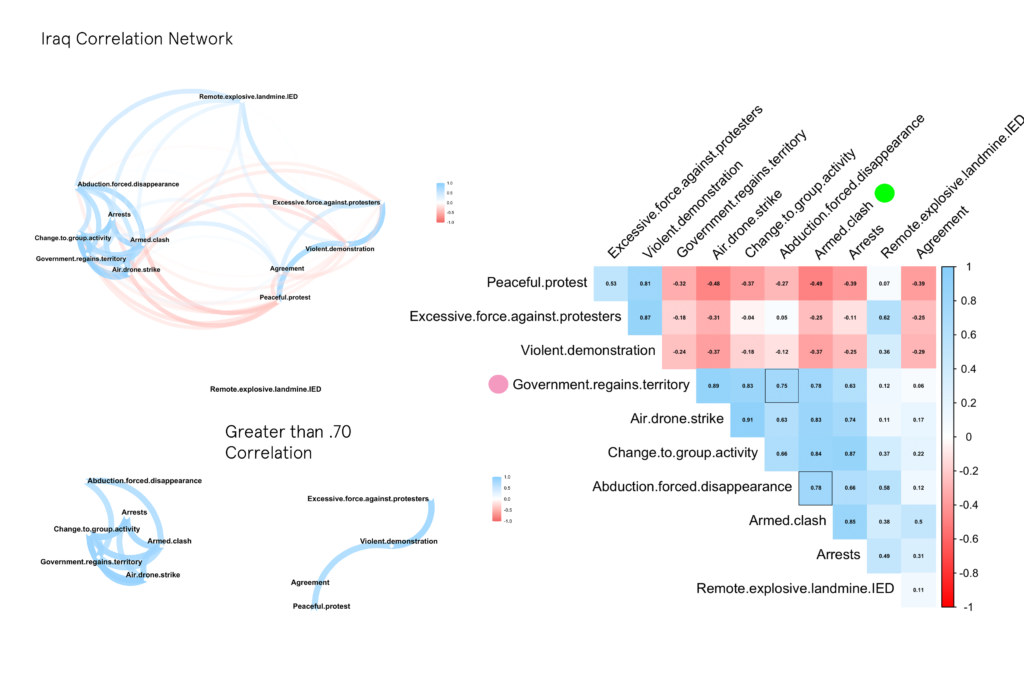

2. Correlation of Event Occurrences to Abductions

Another important aspect of this study to find what kind of events are correlated to the rate of abductions.

Simply stated —– If an events’ rate increases or decreases do abductions as well?

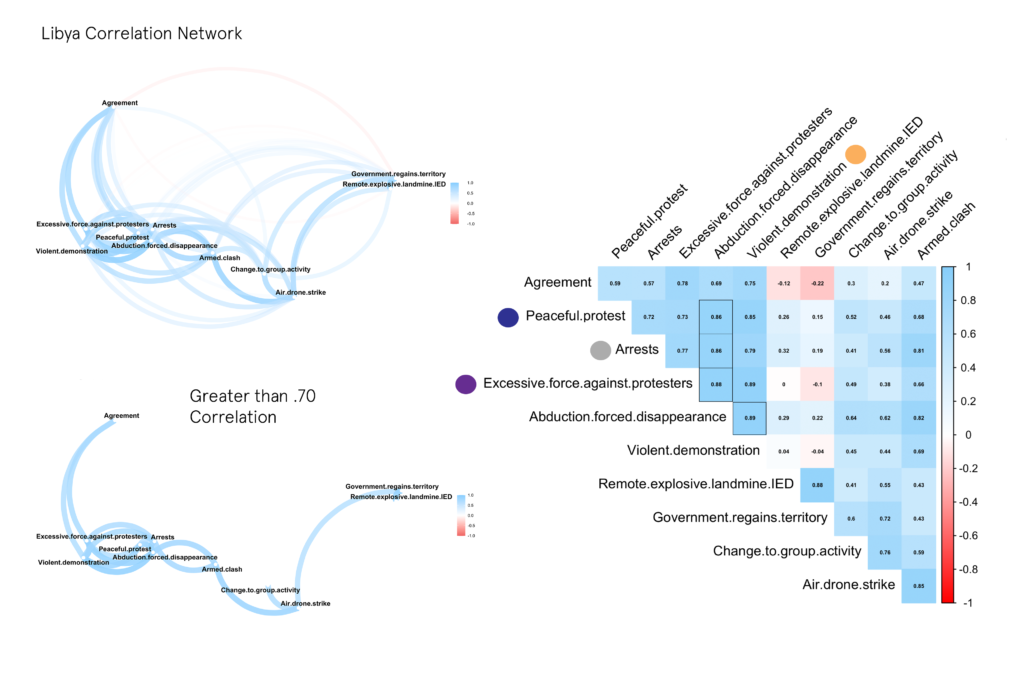

One method of figuring this out is by transforming the data into a correlation matrix and analyzing/visualizing the results in a variety of ways. In this case, a correlation network (on the left) was created that clusters event types according to their correlation coefficient [-1,+1] — with the edges and paths representing the strength of the correlation and the position of the nodes denoting stronger associations. In most cases, a score above .70, and below -.70 indicates a strong positive or negative relationship between two variables. The Correlogram on the right of the network is an easier way to see all the coefficients. I have outlined the highest scores for events related to Abductions.

RESULTS

YEMEN

IRAQ

LIBYA

3. Spatial Regression Model and Coefficient Analysis

This last phase of the analysis is different than the first two in that it attempts to take space completely out of the equation for our events. It is an agreed upon rule (Toblers’ First Law of Geography) that things that occur closer together tend to be more related than things that are further apart.

How do we account for this phenomenon in our data?

Choosing a Neighboring Method

Models which do not adjust for for space can appear to be work well, but in fact they are only modeling spatial dependence — not the variables we are interested in. For Yemen, Iraq, and Libya we must first define what “close” means for our regions. There are two types of neighbors, those based on distance, and those based on contiguity. For this model I have chosen continuity based neighbors.

Continuity neighbors are identified by data that share borders. There are several types of contiguity based neighbors —-but the two most popular are “Queen” and “Rook” (yes! connotations with chess are correct). “Rook” is the type of neighboring used in this study and can be seen below within the Administrative 1 boundaries of the countries. This is a method where adjoining polygons are considered neighbors only if they share a discrete edge (the island outside Yemen will be accounted for later on).

Morans I Test

With this neighboring set, we can use it to form what is called a Row Standardized Continuity Matrix. This is a matrix of spatial weights that can be used to adjust and account for space within the model. Row Standardized allows each neighbor to be divided by the sum of all neighbors in that row.

This will allow for more influence from neighbors that themselves only

have a few neighbors (like our island).

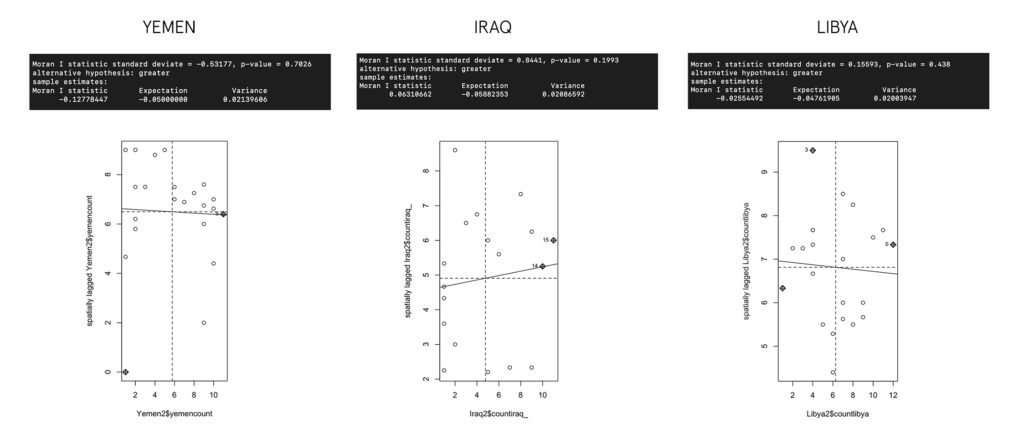

After we have attained the matrix we can use it to test for spatial autocorrelation (the very thing we are worried about) in a method called Morans I. The graph below details the results of the test.

In the case of Yemen, and Libya there is evidence of some negative correlation present—-in Iraq; positive correlation—– however the high P-Value (0.05 and lower is statistically is significant) tell us that there is actually very limited spatial autocorrelation in the three regions. This implies we could very well not account for space, and build a normal regression model and be justified—– but— since I know there is a bit of it present why not adjust for it?

The models below are built across our 11 variables which compare their importance to our event of interest (Abductions) with the spatial weights accounting for auto-correlation (what we want to get rid of). There are two different types of models, and two tests for performance which are detailed below courtesy of the knowledge of Philip Martin (Spatial Statistics Professor– Pratt School of Information).

LMlag Model

Here the dependent variables contain the spatial structure that is “lagged” by applying the spatial weights matrix. This is appropriate if you know the structure of the spatial relationship (i.e. the rental price of a unit will be dependent on the rental price of units in nearby buildings).

LMerr Model

Here we do not know the spatial structure, so we put the structure into an error term instead of the dependent variable. This is appropriate when you do not know the underlying spatial structure in the data (i.e. the height of neighboring trees may influence the maximum height that a new tree can grow). This model most closely applies to our circumstance as we do not know with certainty the underlying variables responsible for the shape of our data.

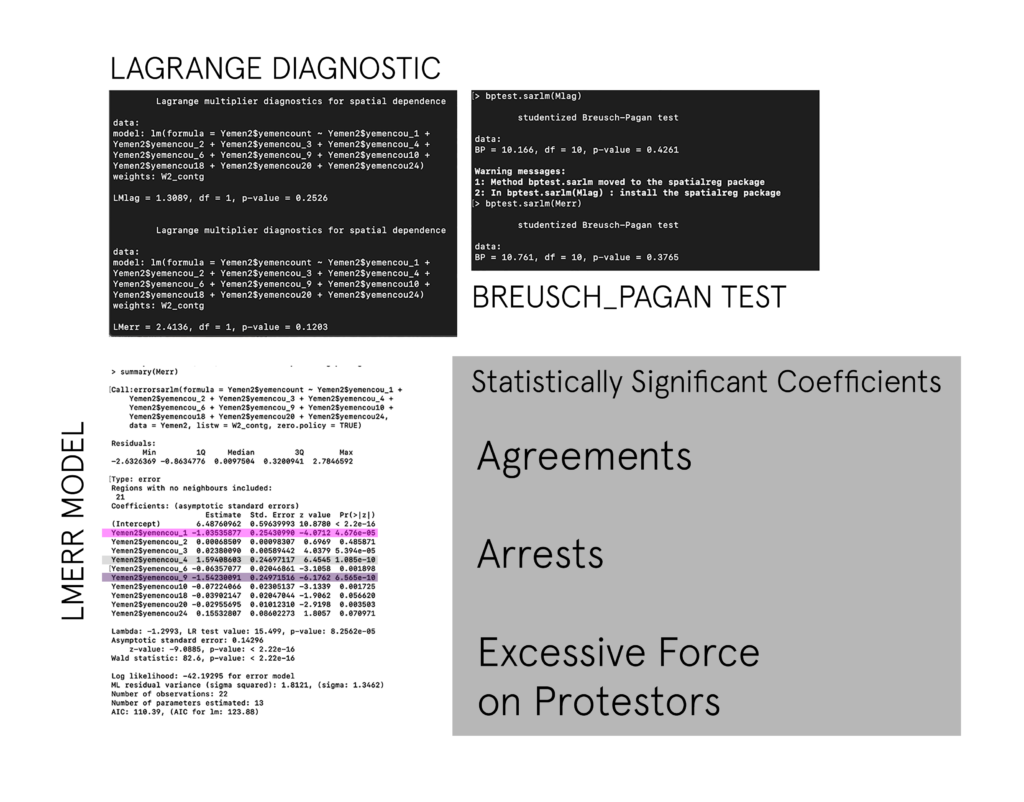

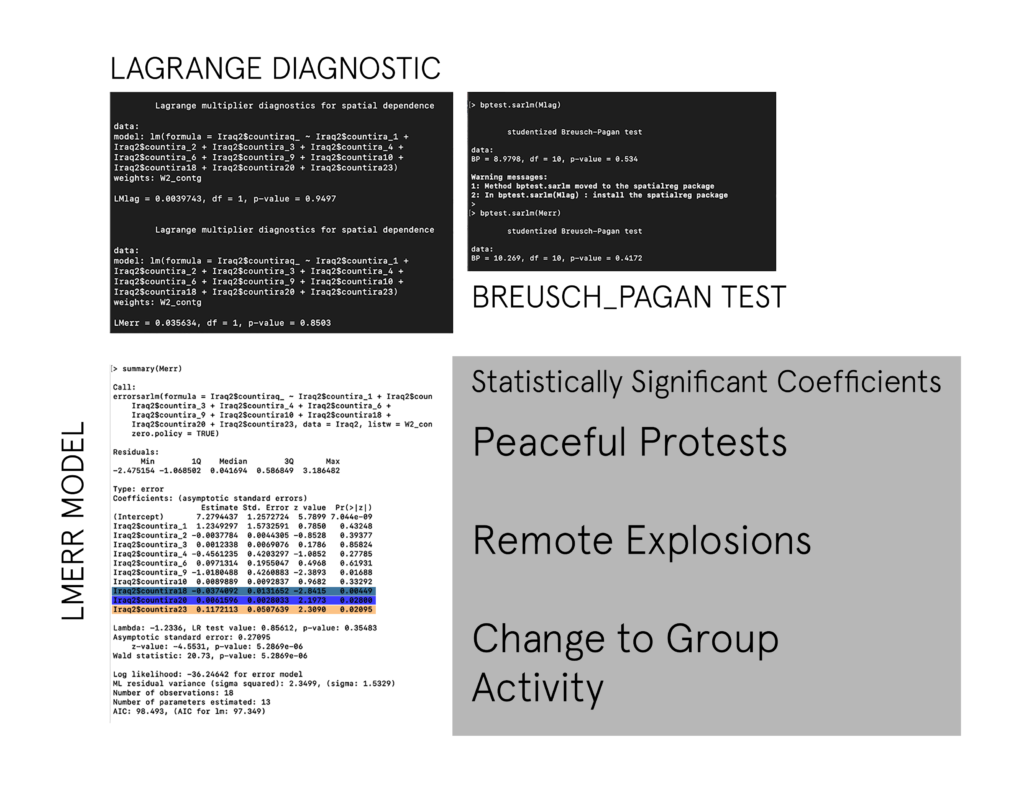

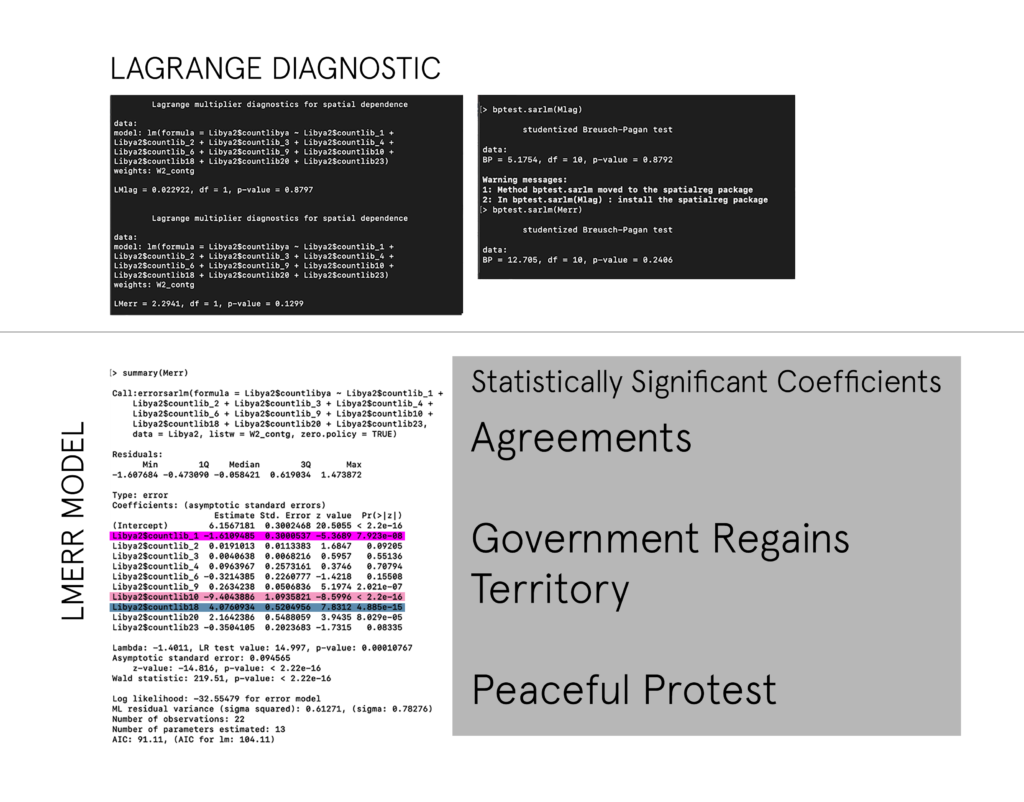

Lagrange Multiplier Diagnostic

This test reports the estimates of tests chosen among five statistics for spatial dependence in linear models. All we are really concerned with here is if the models P-Score is low—(below 0.05) —- then this means that there is enough significance to use both. All models returned scores above .10 — some well above this—- which is not surprising considering the Morans I Test already clarified that there is very little spatial dependence and we wouldn’t have to adjust for it.

Breusch-Pagan Test

We use the BP test to see if there is any significant auto-correlation left after our spatial regression models are created. A high P-Value (above 0.05) indicates that the there is no evidence that spatial autocorrelation exists. In this study both tests indicated that whatever was there for all three countries (however little) is gone! Hooray!

RESULTS

YEMEN

IRAQ

LIBYA

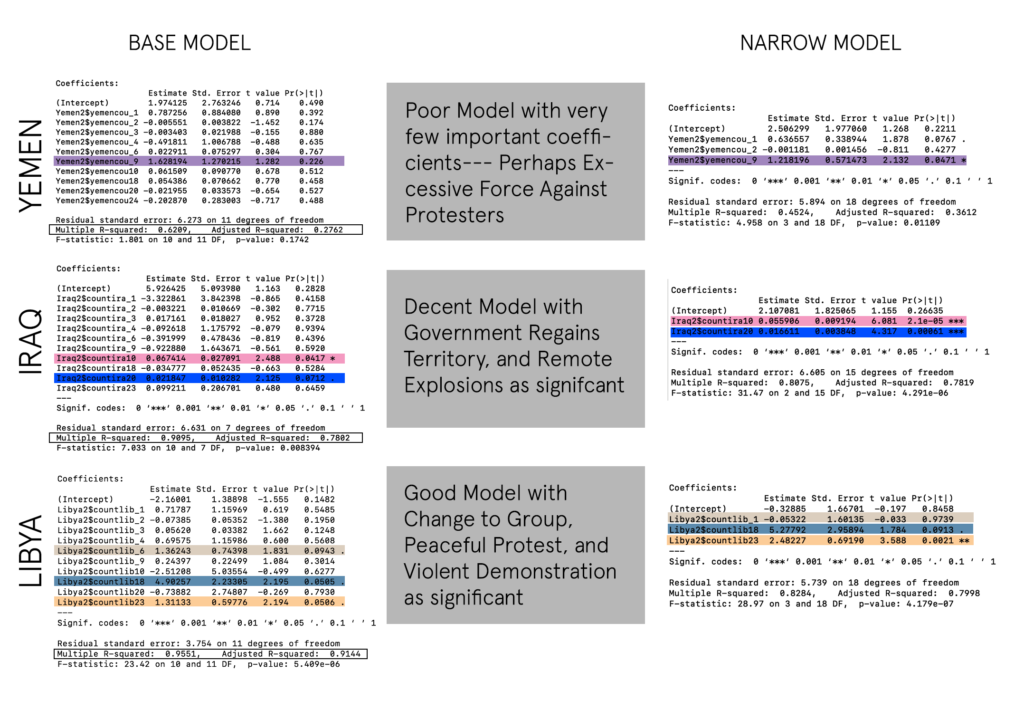

4. Normal Regression Model Without Spatial Consideration

The Morans I Test from earlier illustrated that it wasn’t statistically necessary to adjust for auto-correlation—–however we did anyway. This provides and interesting opportunity to run the normal regression (not adjusted for space) and see how our results differ or are the same with the previous models.

Here are important terms to consult when reading the Model summaries:

R-Squared

This number always lies between 0 and 1— a number near 0 represents a regression that does not explain the variance in the response variable well and a number close to 1 does explain the observed variance in the response variable

Adjusted R-Squared

In multiple regression settings, the R-Squared will always increase as more variables are included in the model. That’s why the adjusted R-Squared is the preferred measure as it adjusts for the number of variables considered.

F-Statistic

F-statistic is a good indicator of whether there is a relationship between our predictor and the response variables. The further the F-statistic is from 1 the better it is.

Residual Standard Error

The Residual Standard Error is the average amount that the response or prediction will deviate from the true regression line.

Coefficient – Pr(>t)

Consequently, a small p-value for the intercept and the slope indicates that we can reject the null hypothesis which allows us to conclude that there is a relationship between the coefficient and our tested variable (Abductions).

RESULTS

Conclusions: Putting It All Together

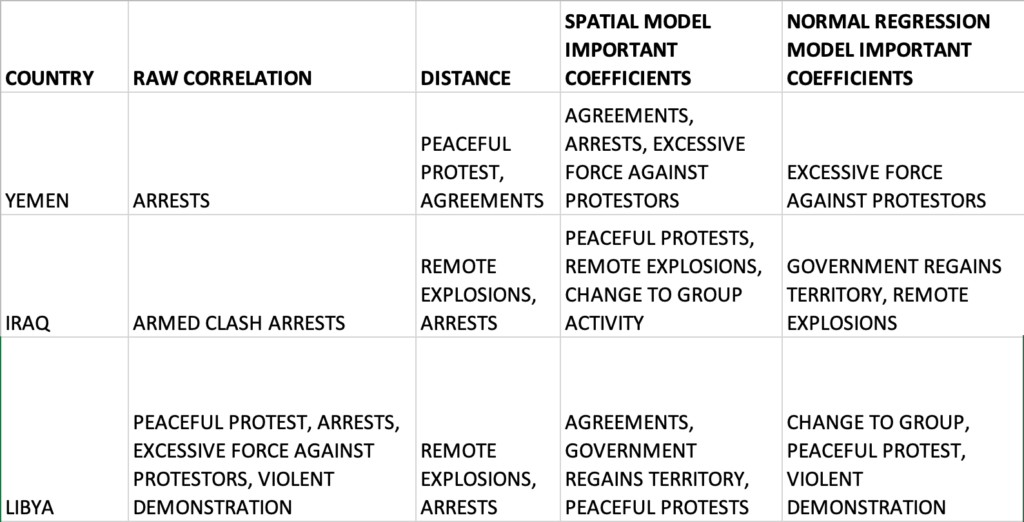

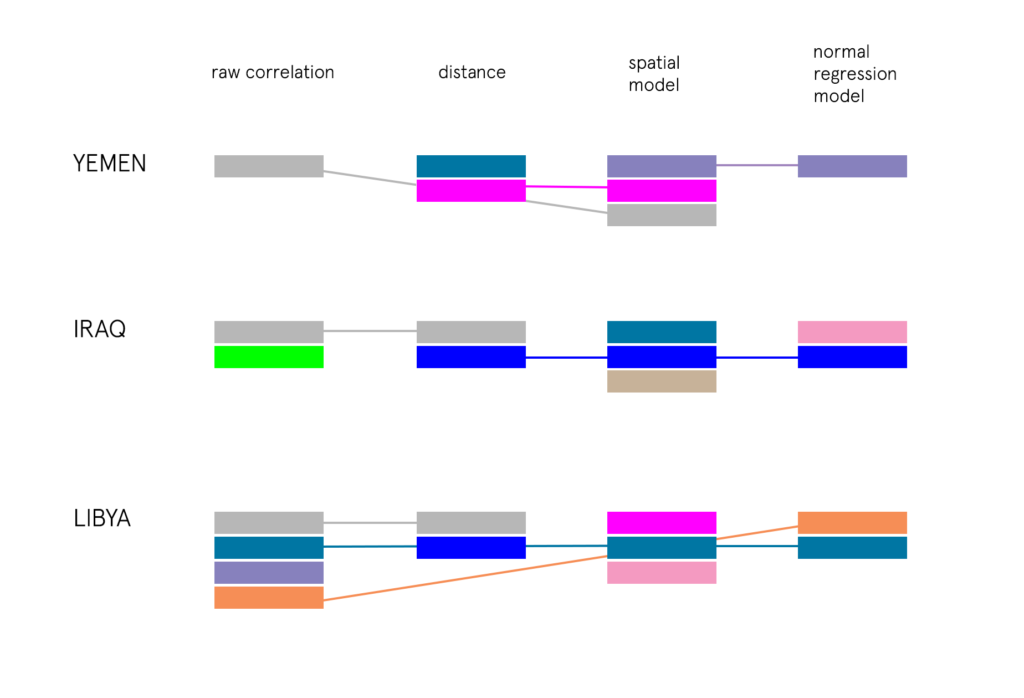

By looking at the results of four facets of this investigation— mainly the important variables and coefficients in each area which prove to be statistically significant—- we can come to some conclusions about factors that heavily influence abduction behavior.

YEMEN:

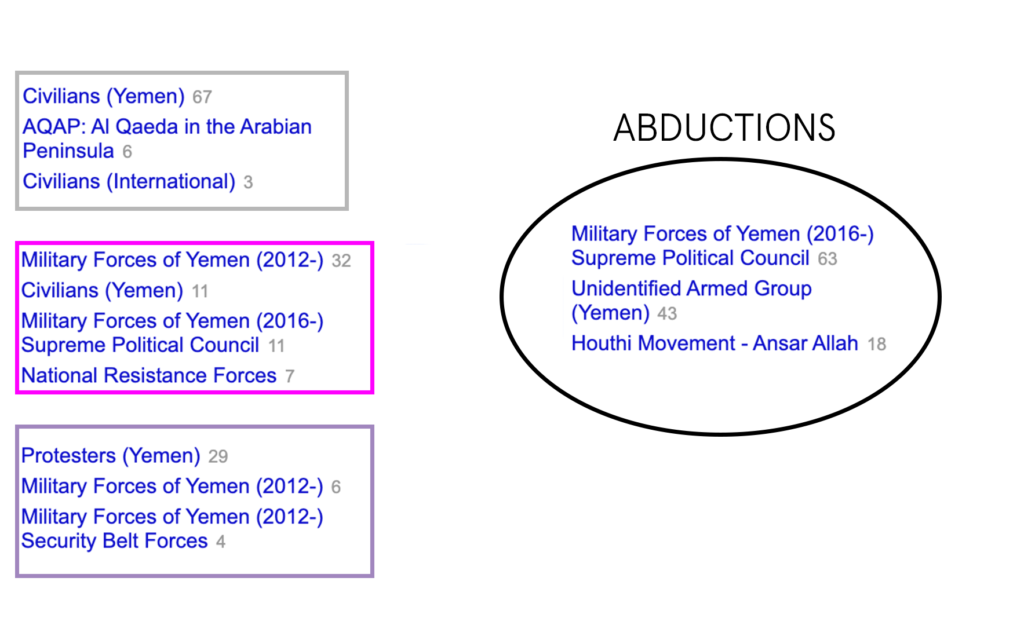

In the case of Yemen, there seems to be enough evidence to implicate Arrests, Agreements, and Excessive Force Against Protesters as contributing factors for civilian abductions. If we look at the top actors involved in abductions in the country we see a large number abductions featuring the Military Forces of Yemen —- in the other events it is also the same. It would be safe to say that where there is conflict between civilians and the military —- as well as agreements —there is also abductions in Yemen.

IRAQ:

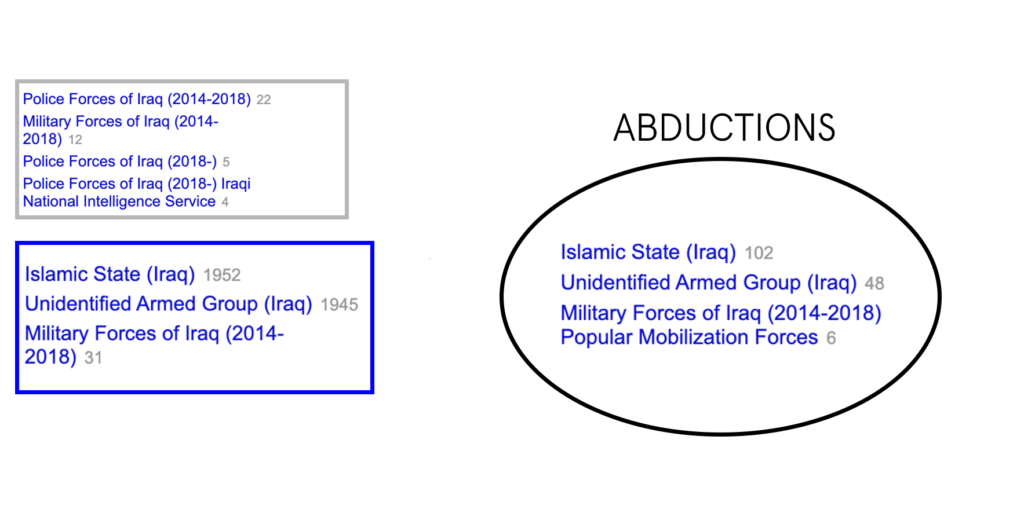

In the case of Iraq, there is a very strong correlation for Remote Explosions, and Arrests being contributing factors for Abductions. By observing the top actors in the events we see a large number of abductions feature the Islamic State, and unidentified armed groups —– this is also echoed in remote explosion events, and arrests which feature a largely militant police force. It is safe to say that where there are arrests and violent attacks featuring explosions between the two groups, there is also a fair amount of abductions in Iraq.

LIBYA:

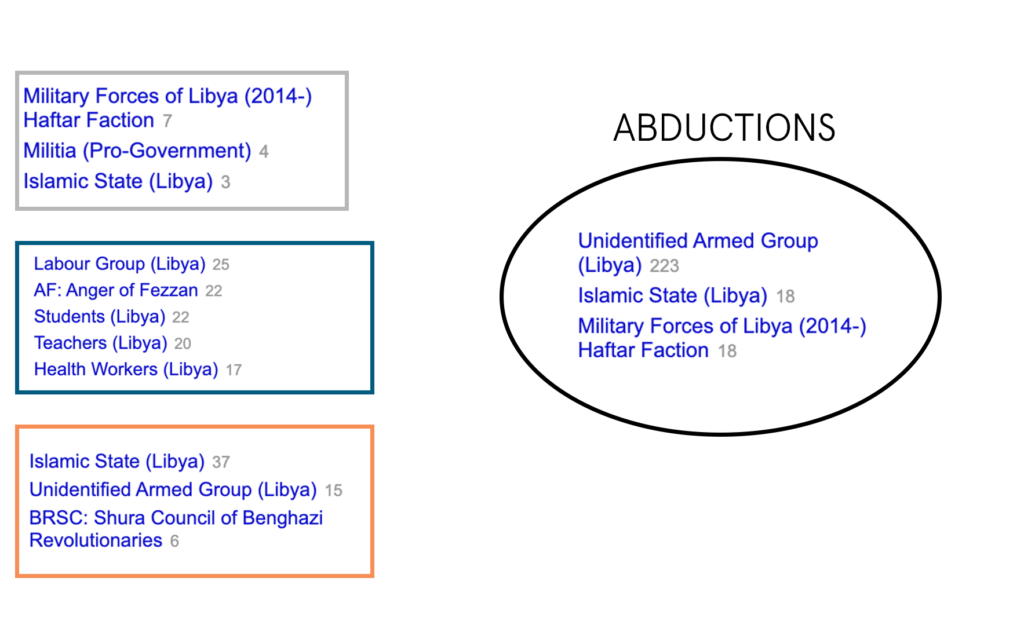

In the case of Libya, there is enough evidence to strongly point towards Peaceful Protests, Arrests, and Violent Demonstrations as important coefficients in occurrences of abductions. A closer look at the top actors provide a more complex dynamic at play involving violent demonstrations by the Islamic State, peaceful protests of civilian groups, and unidentified armed groups. This denotes some conflict between multiple factions and interests within the country— but it is unclear of the exact dynamic leading to abductions of civilians.

Further Research

There are a couple considerations for further investigations not considered in this report.

- Accounting for time, and performing the study for each year

- Using more granular administrative boundaries for the spatial regression model (Admin 2, Admin 3, etc.)

- Involving other countries from different regions as contrast. Different cultures and conflicts will spur more discussion and comparisons.

- Including more event types— there could be events that are more aligned and correlated with abductions that are not included here.